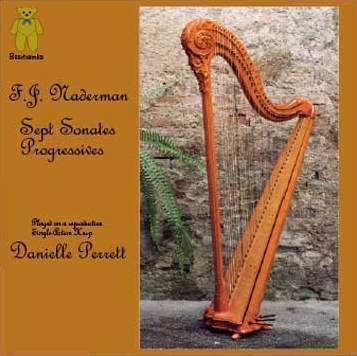

F.J. Naderman ~ Sept Sonates Progressives

(Played on a reproduction 1770s French single-action harp)

Extended CD notes

Extended CD notes

The notes below, with additional pictures, constitute an extended version of those found in the CD booklet – by Danielle Perrett

Paris at the time of the Revolution and immediately after – a time of uncertainty and suspicion, yet a time when appreciation of music showed taste, cultural elegance and a way, like a domestic existence, of temporarily escaping the horrors of the political situation. Many ladies had followed the vogue, which reached its apogee in the form of Marie Antoinette, of learning the harp.

Not to be outdone, Josephine also leaned the instrument and chose as a teacher Francois Joseph Naderman. These ladies turned to the instrument because it reflected their physical charms and because of the diversionary nature of its music, mostly intended for domestic performance. Indeed, men encouraged ladies in this pursuit as a ‘cult of domesticity’ grew up to keep them in their place. Male harp teachers helped to keep them there!

Francois Joseph Naderman, the son of a harp maker and music publisher was the most celebrated harp teacher and player of his day in Paris. His father, Jean-Henri (1735-1799) built many single-action harps (the kind of harp used in this recording) together with his friend J.B. Krumpholtz (1742-1790) who became Francois Joseph’s harp teacher.

Following the deaths of Krumpholtz and later his father, Francois Joseph and his brother Henri (c1780- after 1835) took over the family harp making business, although Francois Joseph was the better performer and Henri devoted himself more to his father’s business. Francois Joseph managed to achieve favour and position with Napoleon, but cleverly, after the Restoration in 1815 he was appointed harpist of the ‘Chappelle et Chambre du Roi’ and then in 1825 was appointed as the first harp professor at the Ecole Royale Conservatoire de Paris where he worked until his death.

He also became a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur. He composed a wealth of literature for the harp, both for himself as a chamber and solo musician, as loyal promotion for the instruments made by family’s harp making business and also as teaching material.

The Seven Sonatas performed on this CD formed the second part of his ‘Ecole de la Harpe published in Paris around 1832 and are cited on the front cover of the earliest available publication by Naderman publishers as being ‘adopted for teaching at the Conservatoire of Music. In other words, as we play these sonatas today, we can envisage Naderman sitting alongside his own students, correcting, encouraging and inspiring them to play.

Each sonata is preceded by a Prelude. We might think this to be a curious thing today, but Naderman was by far from alone in this compositional and improvisatory musical practice. Given that often the music was performed in a salon during an evening of family entertaining; maybe girls sitting gossiping or parents and friends playing cards, the beginning of the piece needed to grab the listeners’ attention.

A short declamatory prelude setting the key and the mood of the work to come was a satisfactory way of announcing the piece without sacrificing any of the first real movement as people settled down to listen. It warmed up the fingers and enticed the ears of the listeners. Even Beethoven was renowned for his ability to ‘prelude’.

All but one sonata contain just two subsequent actual movements whilst no 3 has three movements. Despite being criticised for their lack of depth, many of Naderman’s compositions show dramatic sentiment, and the speed with which he reputedly performed would reflect the great intensity behind works such as Sonata no. 6 of this set. The speed also reflects his technical brilliance: these sonatas are no mere technical studies, but showpieces for the capabilities of the instrument and Naderman’s own virtuosity.

This was a real mission for Naderman, for during his lifetime his family’s business was rivalled by the innovations of another fledgling harp making dynasty – Erard. Naderman had, through his social position and his teaching, considerable influence in the Paris harp world.

The fact that in England the next step on the harp’s evolutionary ladder by Erard was embraced with enthusiasm by players and led to a total change in compositional style ahead of Paris was due to the fact that Naderman managed to discourage his own students from turning to the new fangled double-action harp with increased chromatic possibilities and thwarted much of its progress there until after his death.

Only someone who had lived through the French Revolution could have produced the nervousness of the driven semiquavers in Sonata no 2 in C minor’s Allegro Maestoso first movement. By sheer contrast, classical elegance is displayed in the Andantino con Spiritosecond movement of no. 3 and Tempo di Minuetto and Trio of no 5.

Fashionable styles are suggested in the last movement Rondoletto Anglaise of Sonata no 3whilst the craze for all things Scottish is placated in the ‘Reminizenza’ theme of the second movement of no 6, another Rondoletto marked Allegretto Elegante and we find it also in the last movement of no 4 marked Ecossaise Rondoletto Allegretto con Sentimento.

In his own way, the first movement of no 6 reveals Naderman to be standing on the threshold of Romantic music with its dramatic intent, whilst in no 7, the ‘Reminizenza’ Rondoletto Allegretto last movement reverts to a wit not out of place in Haydn’s writing. The rondo was the most popular and fashionable form for the last movement of a work at that time.

Harp by Jean-Henri Naderman, Paris, 1771. Single-action pedalharp with crotchet mechanism, 35 strings Ab1 – bg3. [private property; photo © Beat Wolf]

Some of the criticism of Naderman’s lack of depth may be due to the fact that his first movements are not in what today we would describe as a conventional sonata form where the themes are developed in the middle of the movement with every last possibility wrung out of them in the manner of his contemporary Beethoven. Here there are series of episodes instead with no development of themes, protracted to greater or lesser extent.

The comparisons and parallels with Beethoven are justified for, like Beethoven and the rest of Europe, Naderman was held in thrall by the Emperor, dependent on his whim for possible success and stability.

In some ways, at the time, Naderman was the more successful composer – he after all, managed to hold on to changing political patronage. In his own way, he was struggling with containing dramatic power within the confines of the instrument and the form and language of the pieces. Words such as ‘disperato’, ‘sentimento’ and ‘fieramente’ pepper his writing just as often as ‘elegante’.

If Naderman’s family had not been harp makers and Naderman had allowed himself to embrace the possibilities of the double-action harp, who knows where that might have taken him?

Louis XVI harp built 1998 by Beat Wolf, Schaffhausen, after Parisian Masters of the late 18th century. Single-action pedalharp with crotchet mechanism, 39 strings

F1 – bb3.

[photo ©Antonio Idone]

The single-action harp was the first popular solution to produce a harp where its single row of strings could be raised or lowered by one semitone in pitch via mechanism at the tops of the strings. This was linked to foot operated pedals at the bottom of the instrument. The mechanism approximated to the effect of depressing the fingers on the fingerboard of a violin or the frets of a guitar, although unlike these instruments only one rise or lowering of pitch was possible.

The instruments were beautifully carved, gilded and decorated in the fashion and styles of the day. Some instruments showed popular Chinoiserie decoration. When the Empire came about, so did an Empire style of decoration, somewhat less frivolous than the previous dancing maidens and ornate scrolls which had decorated harps.

The double action harp, had, as its name suggests, two possible moves of the mechanism for each string and suited perfectly the increasing chromaticism and changes of keys of Romantic music. It was this instrument for which subsequent composers wrote, although the single-action harp was still used as a teaching and domestic (as well as folk) instrument.

After Naderman’s death it prevailed in Paris over the single-action. Naderman’s output is the last real blossoming of repertoire for the older instrument and was struggling against becoming anachronistic in style like the instrument itself.

The harp used on this recording is a remarkable reproduction by Swiss harp maker Beat Wolf, of a harp made by Naderman, Paris in the 1770s. Authentic in tone, tension and decoration, it was a sheer joy to play. Hearing the captivating sounds created by this harp was like looking at a painting with layers of brown varnish removed – the sparkle and brilliance shone through.